When I was eleven, our home burnt to the ground in the Bel Air fire, and everything we owned burned to ash. Shortly after my mother moved us to an apartment in Brentwood, a mammoth carton arrived and was placed in the center of the living room. My mother cut it open and urged me to look inside. I sat cross-legged on the avocado green carpeting, and discovered bundles of garments; Bermuda shorts, blouses, sweaters, and shirts.

I quickly shed my worn trousers and stepped into a new outfit, dancing about as I zipped myself in. My mother watched, and echoed my childish yelps of elation.

“Mommy, who are these from?”

“They’re from your Aunt Millicent.”

“Who is she? I don’t remember her.”

“You were a little girl. She loves you very much.”

Years later, my father, Allen Smiley, called and told me to come over to his apartment in Hollywood.

“Why Dad?”

“Millicent is coming by; I told you she moved here, didn’t I?”

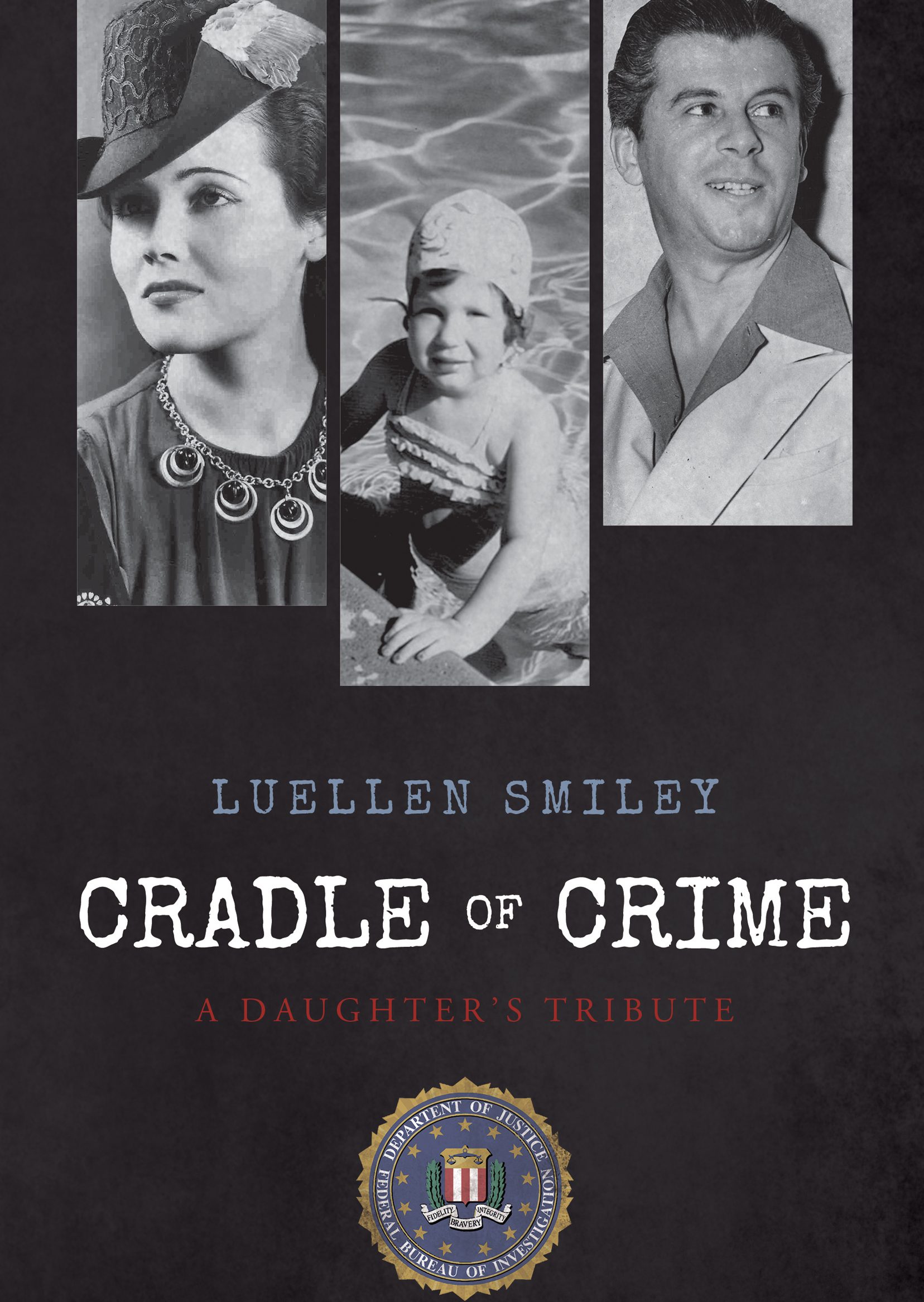

I’d learned Millicent was Benjamin Siegel’s daughter, and Ben was my father’s best friend. Dad was sitting on the same chintz covered sofa the night Ben was murdered.

“You mean Ben Siegel’s daughter?”

“Don’t refer to her that way ever again; do you hear me? She is Aunt Millicent to you.”

When my father answered the door, I watched as they embraced. Millicent had tears in her eyes. She walked over to me, and took my hand. I looked into her swimming pool blue eyes and felt as if I was drowning. She sat on the edge of the sofa and lit a long brown Sherman cigarette. I studied her frosted white nails, the way she crossed her legs at the ankles, her platinum blonde hair, and the way her bangs draped over one eye. What impressed me most was her voice; like a child’s whisper, her tone was delicate as a rose petal.

I spent the rest of that afternoon memorizing her behavior. She emanated composure and a reserve that distanced her from uninvited intrusion.

Over the next few years, Millicent and I were joined through my father’s arrangements, but I was never alone with her. When he died in 1982, she was one of only three friends at his memorial service.

As the years passed, and my tattered address books were replaced with new ones, I lost Millicent’s phone number. I had been researching my father’s life in organized crime, and had gained an understanding of my father’s bond with Ben Siegel. My discoveries were adapted into a memoir and recently into a film script about growing up with gangsters. During this time, I had reconnected with several of Dad’s inner-circle, but Millicent was underground, and now I understood why.

Last year I received an email from Cynthia Duncan, Meyer Lansky’s step-granddaughter. She told me about Jay Bloom, the man behind the Las Vegas Mob Experience, a state of the art museum that will take visitors into the personal histories of Las Vegas gangsters. Cynthia contributed her significant collection of Meyer Lansky memorabilia, and assured me Jay was paying tribute to the historical narrative of these men by using relatives rather than government and media sources. She wanted me to be involved.

Despite my apprehensions about the debasing and one-sided publicity that characteristically surrounds gangster history, I contacted Jay. In his return note, he invited me to participate, and added, “Millicent would like to contact you.”

A month later I was seated in Jay’s office waiting for Millicent. When she walked in, I stood to embrace her, and this time the tears were in my eyes.

Millicent’s voice was unchanged and so was her regal posture. “Our fathers were best friends, attached at the hip. Your Dad was at the house all the time. I’ll never forget when he and my mother met me at the train station to tell us about my father’s… death. Smiley was very good to us. My mother adored him too.”

Jay took me on a tour of the collection warehouse, and the history I’d read about unfolded before my eyes. The preview room was like a family room to me, because some of the men had been my father’s lifelong friends and protectors. I stopped in front of the Ben Siegel display case and saw an object that was very familiar.

“My father has the identical ivory figurine of an Asian woman. I still have it.” So much of their veiled history was exposed; between these two men was a brotherly bond that transcended their passing and was even evident in their shared taste in furnishings.

Jay showed me a layout of the Mob Experience in progress. I turned to him and asked, “Is it too late to include my father? All the rooms are assigned.”

“Millicent and I already spoke about it. She wants your Dad in Ben’s room.”

After I returned home, Millicent and I talked on the phone.

“Your father belongs in my Dad’s room. They’ll just have to make Mickey Cohen’s room smaller.”

“My father hated Mickey,” I said.

“So did mine! When are you coming back? I’ll kill you if you don’t become part of this.”